Okay, tell me if this is familiar:

First thing you looked for when you started Anki is pre-made/shared decks.

You went and downloaded them into your Anki — thinking it would save you time.

SURPRISE! 1,000 cards you know NOTHING about.

Now you’re overwhelmed with the number of cards, and don’t know how to actually navigate the damn thing.

You start to think, “Are these Anki users just plain psychopaths?!?!?”

But deep down you know the answer:

You know that creating effective flashcards is the solution…it’s just taking you a LONG time to make them.

So in this post, I’m going to share with you the most important principles I learned creating 4000+ flashcards for my board exams.

In this article, you’ll learn:

✅ Why the creating effective flashcards actually save you more time than you think

✅ The secret to actually enjoying your reviews (rather than drowning in it)

✅ The 3 principles that tell you how to practically create an effective flashcards in seconds

✅ How to think right about flashcard-making so you can remember more and have a life outside of studying

Why Creating Your Own Cards Actually Save You Time (It’s NOT passive!)

When you think about creating your own cards, the first thing that comes to mind is this:

“I don’t want to keep spending this much time on something that feels so passive.”

I understand it FEELS like a waste of time, and you WANT to make it faster.

But effective Anki learners know that this is a mistake — for a few reasons:

- The intermediate processes of card-making is effective studying. It combines effective active learning practices AND retrieval practice in just one process. NOTHING is more time-saving than that.

- Finding relationships to test, and generating the exact insight to make flashcard for → elaborative encoding

- Transforming that insight into question form → generation effect

- Retrieving the answer from your mind after writing down the question on the “Front” side → retrieval practice (or commonly known as “Active Recall”)

- Making your OWN questions shifts the focus on processing the material. You can’t make good flashcards about Physiology if you don’t know anything about the relationships.

- You can bring undivided attention to making EACH idea more memorable. Because you are the one learning the ideas before creating the prompts, you can add details that are relevant to YOU personally and make them easier to recall in the future.

- For example, personal relevance or examples at the “context” part (You’ll see later)

- Memory techniques + mnemonic flashcards

Meaning, as an Anki learner, skipping the process of making your own cards makes you automatically skip ALL these 3 benefits.

Plus, there’s another time-saving difference here that most people don’t realize.

Effective Flashcard Make Reviews Enjoyable and FAST

Yes, I’m saying that people who use Anki daily aren’t a bunch of sadists and psychopaths who just brute-force themselves to finish their daily due cards.

They’re actually having a good time! (Well, at least I did.)

Because you see, if you’re constantly drowning in reviews, or if somehow you keep forgetting your flashcards and it’s taking you HOURS just to learn new ones…

The solution is NOT to “limit your daily cards” or use some goddamn joystick to make reviews exciting, like OH MY GOD I CAN’T STOP REVIEWING MY WALLS OF TEXT BECAUSE OF MY JOYSTICK.

No, no, no.

The solution is to have cards that make you feel like you’re making progress.

Your goal is to actually start enjoying the reviews.

If you’re not enjoying it, DO NOT expect yourself to sustain it!

Practically speaking, when you create effective flashcards, it start a compounding effect:

- You reduce the number of flashcards you need to make when you learn key ideas instead of just “bolded terms” because you can infer the details from key ideas.

- Get your cards right the first time you review them. Well-learned ideas are WAY easier (and thus, faster) to recall than meaningless ones.

- Avoids “Ease Hell”. Ease Hell is the Anki user’s nightmare; it’s when you see too many cards with extremely low intervals because the ease factors are too low. By learning first, you don’t press “hard” as often and thus can avoid modifying the individual ease factors as much.

- Reviews become fun. You feel like you’re actually winning. You start looking forward to making cards, and also reviewing them. And this cycle repeats all over again.

And efficiency-wise, if you could save just 1 hour per review session because you made good quality flashcards…

You’ve just saved 7 hours per week on dreaded reviews.

Which means you CHOOSE how to spend that extra time 🙂

Before Anything Else: You NEED a Screenshot + Annotation Tool

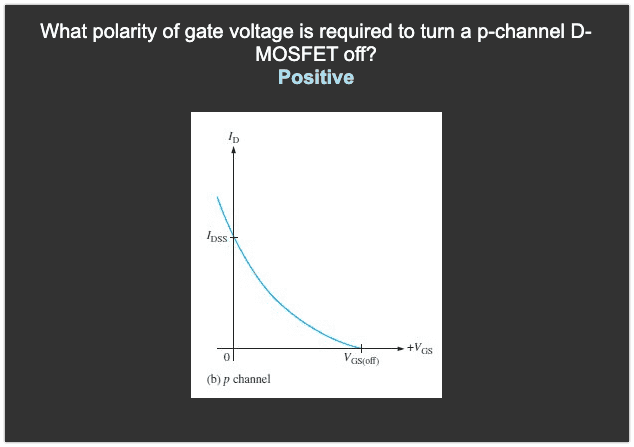

You want to be able to make cards as you’re studying your materials, and instantly make cards with screenshots like these:

SERIOUSLY. If you don’t have this, you’re missing out 🙂

For Windows, best one I’ve used is ShareX — back when I was a Windows user.

For Mac, I like either CleanShot or Monosnap. CleanShot is paid, but it’s SO good. Monosnap is “okay” but the shortcuts aren’t intuitive and feels slow.

How to Make Effective Anki Flashcards in Seconds – Quick Overview

What you need to know about creating effective Anki flashcards is that it’s more about “how you’re being tested with what you know” than the features.

NOT about add-ons.

NOT about card types.

NOT about custom fields.

And it just so happened that there were best practices for doing that, which we’ll go through in a bit.

Let’s break this down into a few “layers”:

- Structure. This deals with what your card LOOKS like. What card type to use + the elements inside each card.

- Content. This is how you form the question-answer pairs. How you turn information into questions, how long your questions should be, etc.

- Integration. This is how your flashcards fit the bigger picture. If you’re not integrating, if you’re just stuck thinking in terms of Structure, you’ll never get anywhere.

Why the 3rd layer? Well, know that you’re dealing with KNOWLEDGE, not flashcards.

At the end of the day, it’s all about what you could RECALL and APPLY out of what you have learned — not just what you remember.

Part 1. STRUCTURE – Best Card Types + How to Structure Your Flashcards

First off, let’s talk about Card Types. In my experience, here’s where their strengths lie:

- Basic type – extremely flexible for remembering almost anything except locations in images. I’ve used a basic Q&A card for

- Facts

- Lists

- Complex concepts – cause and effect, etc.

- Formulas

- Patterns/Mnemonics (ex: “What’s my mnemonic for signal classification?”)

- Conditional facts (ex: “When do you use this formula vs this one?”)

- Image Occlusion – for labels/locations in images

- Cloze card – best for memorizing a sequence of words that have fixed structure, like lyrics or poems

I’ve climbed my way to the top of rankings for my boards, and I’ve NEVER used other card types.

Haven’t even seen them, or created a new card type for myself!

So what do I recommend?

A bread-and-butter structure for flashcards that are fast to answer.

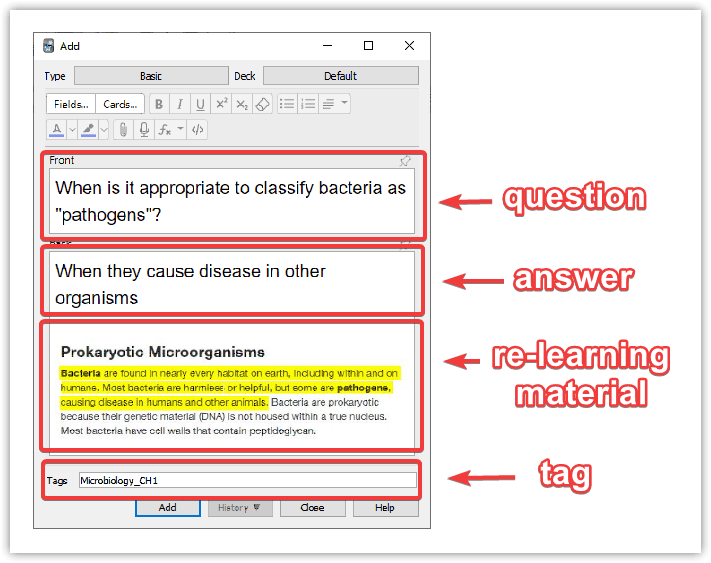

I call it the “10-second flashcard” — a BASIC type flashcard that consists of 4 components:

- The question [FRONT]

- The answer [BACK]

- The supplementary context [BACK]

- The tag (optional)

The most important is that the FRONT of your card has to be a question, not a statement.

For example, “Mitochondria”— because your brain will be like, WHAT THE F*CK ARE YOU EVEN ASKING?!

Specific cues are much faster to recall, so always create specific questions. We’ll get into this later.

For the supplementary context, this could be:

- Actual Image (e.g. Diagrams)

- Written/Visual Examples (e.g. from your notes!)

- Mnemonics (e.g. PVT TIM HALL)

- Highlighted source [[202105051141]] (e.g. Lecture Slide, passage from book)

- Connected ideas (ex: “This is similar to XYZ concept, because X also leads to Y → a simple comment like this)

- Personal Relevance. Basically how this relates to your own experiences, which is basically connecting to more robust memories.

You do NOT need other card types, aside from Image Occlusion. But that’s a topic for another day, since it’s a specialized type.

Part 2. CONTENT – Convert Your Learning into Questions That Test Understanding

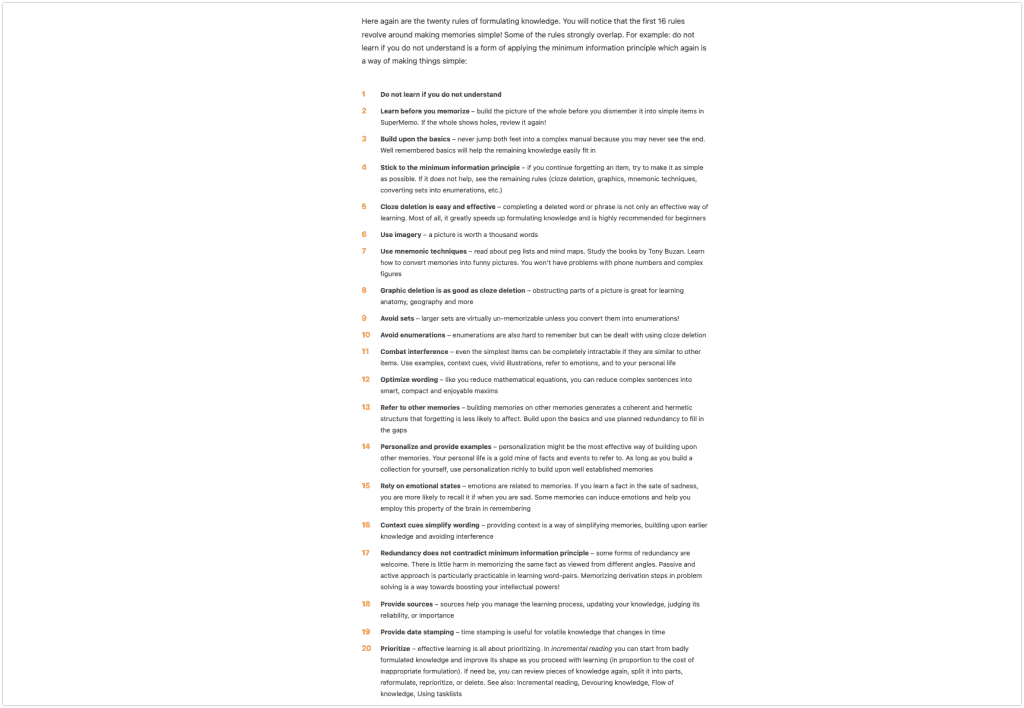

When I started studying about creating better flashcards, I stumbled upon this article called 20 Rules of Formulating Knowledge — which is said to be the GOSPEL of card creation.

Now, I don’t know about you, but having 20 rules doesn’t exactly feel “follow-able” to me. It DID help. Don’t get me wrong.

(That’s just my opinion, anyway. But it’s a good read nevertheless)

But I figured I’d have to extract the core principles surrounding this.

I wanted my flashcard creation process to be as SIMPLE as possible, and seamlessly integrate with my study process.

- Materials ⇒ Mental Processing ⇒ Flashcards

- Lectures ⇒ Mental Processing ⇒ Notes ⇒ Flashcards

- Textbooks ⇒ Mental Processing ⇒ Flashcards

ALL without overthinking the process, simply because I would benefit more from reinforcing what I learned instead of dabbling with features. So that’s exactly what I did.

I boiled down the 20 rules to three simple principles — which I’ll encode as the “EAT” principles of effective flashcard creation:

- Encoded. This is the most important principles of “Learn before you memorize” and “Build upon the basics”. You ONLY make flashcards from things you have ALREADY learned. Anki is merely a practice scheduler, not a magic tool for long-term retention. If you haven’t learned ANYTHING, you’re not strengthening ANY connections—they nothing to strengthen in the first place.

- Atomic. This means your cards are small and specific enough to help your memory retrieve information. Recall is basically a “search process” in memory. Vague search terms make LOTS of results, and you’ll struggle to answer. On the other hand, specific search terms give you FAST answers.

- Timeless. This means you are creating cards that HELP your future self. We’re in this game for the long-term, and the last thing you want is having incomprehensible cards that make your future self suffer.

Of course, implementation is different.

I’ll demonstrate with a quick flashcard creation workflow for a lecture slide.

Step 1. Put your material and the Anki “Add Card” window side-by-side

You want to be able to:

- See the material as you’re creating your questions (effectively using them as “cognitive scaffolds”)

- Take a screenshot of the material, and be able to annotate them quickly

Step 2. IMPORTANT: After you get one insight, create a “Why/How/When question” that tests your understanding of that one insight alone

Notice, I did NOT specifically say: “when you see something that looks important”

Because frankly you don’t need to make cards for EVERYTHING!

Now, this doesn’t have to be complicated. It’s better to show by example:

- What I learned:

- If you have 2 or more devices exchanging data through some medium, that’s data communication

- Why/How/When Question, could be:

- How is data communications different from all other types of communication?

- When can you say that 2 devices are undergoing data communications?

- Why – it’s hard to think of a Why question here. That’s totally fine.

Obviously, a “What” question is fine. But practically it’s so much better to think about Why/How/When first because that’s how you can think of questions that test UNDERSTANDING rather than RECALL.

And when you can test understanding, it strengthens CONNECTIONS of concepts, rather than just your ability to recognize the question and regurgitate answers from the book.

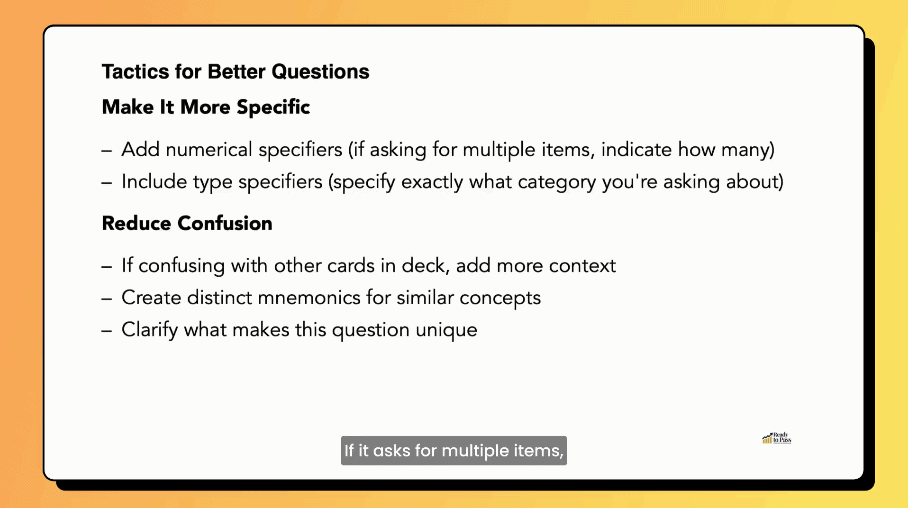

Step 3. Add specifiers and supplementary context

So usually, you won’t be able to make atomic questions right away — it’s normal, we’re not used to doing that.

But the good news is you’ve ALREADY implemented the principles.

So NOW is the time for tactics — either make your questions more specific, or more memorable/non-confusing.

Some examples:

- NON-ATOMIC VERSION: How is data communications different?

- ATOMIC VERSION: How is data communications different from all other types of communication?

- NON-ATOMIC VERSION: How can you tell if something is a pathogen?

- ATOMIC VERSION: When can you classify a bacteria as a pathogen?

- NON-ATOMIC VERSION: Describe Unipolar Junction Transistors ⇒ you want to refactor this into parts that allow you to describe it

- Where does the p-n junction of the UJT form?

- Why does a UJT require high-resistivity between the rod and Ohmic base contacts?

- Why do UJT resistors have n-type high-resistivity silicon slabs?

Notice how I broke a BULKY question down into atomic questions that are much faster to answer. If you want more examples, check out this post.

This is KEY to making your reviews more efficient, and also key to remembering massive volumes of information.

Now let’s check:

- Is the question testing an encoded piece of information? CHECK

- Is the question atomic? CHECK

- Is the question something my future self would understand? CHECK

You don’t even need to mentally go through this checklist.

If you follow this similar process, you’ll be able to create effective flashcards in just seconds.

What to expect: This process will seem very slow at first, but once you get used to it, you’ll be able to process your materials into effective cards without even taking notes—which means EVEN MORE saved time!

Part 3. INTEGRATION – The Bigger Picture

At this point you have already created effective flashcards. Congrats!

But of course, we’re not yet done. Effective flashcards are a MEANS to a goal. Our goal isn’t to make effective flashcards, is it?

The goal is to build knowledge—and do it without wasted movement.

Which means your process has to align with that goal as well.

Some of the big problems I hear even intermediate Anki users say are:

- They can’t “see the big picture” when they study with Anki

- How do I use Anki for [insert some weird thing here]

- How do I make a card type for [insert the same weird thing here]

And I understand that it could somehow feel like Anki has become our ONLY way to learn effectively, as an Anki Practitioner.

But that’s not true!

First of all, you don’t need LIMIT yourself to just Anki.

Let me ask you: What’s stopping you from using other techniques?

NOTHING, right? And you don’t have to limit yourself to just making flashcards, either.

Think in first principles—all that Anki is doing is to help you schedule your practice.

And since practice requires specificity, then you can DESIGN your own learning workflow to fit that exactly.

- Losing the big picture?

- Do “big picture recall” sessions once per week

- Use chapter objectives to test your understanding

- Create mindmaps from scratch as a PRACTICE for recreating your understanding

Second, think like a learning strategist.

Ask yourself, “How can I adapt my ENTIRE learning system for my goal?”

- If I’m required to read TEXTBOOKS, then how can I create an Anki workflow that deals with textbooks?

- If I’m required to learn from LECTURES, then how can I create an Anki workflow that deals with textbooks?

- If I’m required to learn SKILLS, then how can I create an Anki workflow that deals with textbooks?

When you start INTEGRATING, you’ll realize that leveling up your Anki mastery RARELY about optimizing your settings or achieving a “target retention rate”.

Epilogue – Effective Flashcards As “Time Assets”

You now have the tools to make effective flashcards. But like any other practical advice, the only thing that will make lasting change is when you change fundamentally how you think about it.

“Inside-Out Transformation”, as I’ve learned from Stephen Covey.

You see, most people think that flashcards are something to “do as fast as you can”, but that’s only because they approach things with a Time Debt mindset. That’s why they fail to reach their learning potential.

Patrick McKenzie, a programmer who runs 4 software businesses, said it best:

Most people think, intuitively, time always rots. You get 24 hours today. Use them or lose them. The foundation of most time management advice is about squeezing more and more out of your allotted 24 hours, which has sharply diminishing returns. Other self-help books exhort you to spend more and more of your 24 hours on the business, which has severely negative effects on the rest of your life (trust the Japanese salaryman!)

And this penetrates just about EVERY efficiency advice out there—including studying.

I propose an alternative: a Time Asset mindset toward flashcard making.

To further quote McKenzie:

Instead of doing either of these, build time assets: things which will save you time in the future. Code that actually does something useful is a very simple time asset for programmers to understand: you write it once today, then you can execute it tomorrow and every other day, saving you the effort of doing manually whatever it was the code does.

If you currently think this is a waste of time, pay close attention as I share with you how this works out with Anki:

You write a GOOD flashcard once, it can help you remember tomorrow and every other day, saving you the effort of going back to what you’ve already covered and the pain of flashcard hell.

(Read that again.)

To put it concretely, you can simply think of your flashcards as “idea seeds.”

They’re “idea seeds” that eventually grow and root themselves deep in your memory, and they give high-quality “harvests” when you tend to them each day they require nutrition.

Problem is, bad seeds always turn into bad plants.

Put plenty of them in your land and, without you noticing, more hard work will yield more of these bad harvests. Like:

- Looping through the same cards every review

- Taking a LONG time to finish due cards because your cards are too vague

- Having to go back from scratch on a material you’ve already studied before

- Re-taking an exam because you failed to remember stuff when it matters most; or worst of all

- Losing potential income

By the end of it all, you’ll come to realize only one conclusion:

I should’ve planted those good seeds sooner.